Unlike our customary newsletters, this week’s is more personal. It promotes a Netherlands crowd-funding campaign for a book about the Polaroid portraits that Bettie Ringma (1944–2018) and I took in Amsterdam in 1980. Writer Leonor Faber-Jonker is both the force behind the book and the fundraiser. Selling Polaroids in the Bars of Amsterdam,1980 is all set to go, but just needs a little help to cover printing costs. Please visit the Voordekunst crowd-funding page to learn more and contribute.

For me 1980 was quite a year. Bettie and I lived on a houseboat on the Prinsengracht opposite the Anne Frank House, paying our bills by making nightly excursions through Amsterdam’s entertainment districts and selling instant photographs for 6 guilders each. Most of the photos scattered into the night, but after we arranged an exhibition in a small Amsterdam gallery, Polaroid provided us with a case of free film to take additional shots. We soon had our own collection of over 350 Polaroids.

When the weekly magazine Nieuwe Revu published an article about our exhibition we became genuine celebrities. Strangers on the street greeted us by name, and some even followed us as we made our picture-taking rounds. In 2019 the bulk of the collection was purchased by the Amsterdam City Archives where the originals are now preserved. Selling Polaroids in the Bars of Amsterdam, 1980 is scheduled to be published in The Netherlands by Lecturis in late May.

The Voordekunst fund-raising campaign is in both English and Dutch. Please click and donate.

Selling Polaroids in the Bars of Amsterdam, 1980 is a bi-lingual hardcover book with 200 photos and a narrative about the experiences Bettie and I had during a very memorable year. It includes two scholarly essays: the one by Mark Bergsma analyzes the photos as historical documents; the second by Leonor Faber-Jonker looks at the photos from an art perspective. The book is designed by Maud van Rossum. It is published by Lecturis.

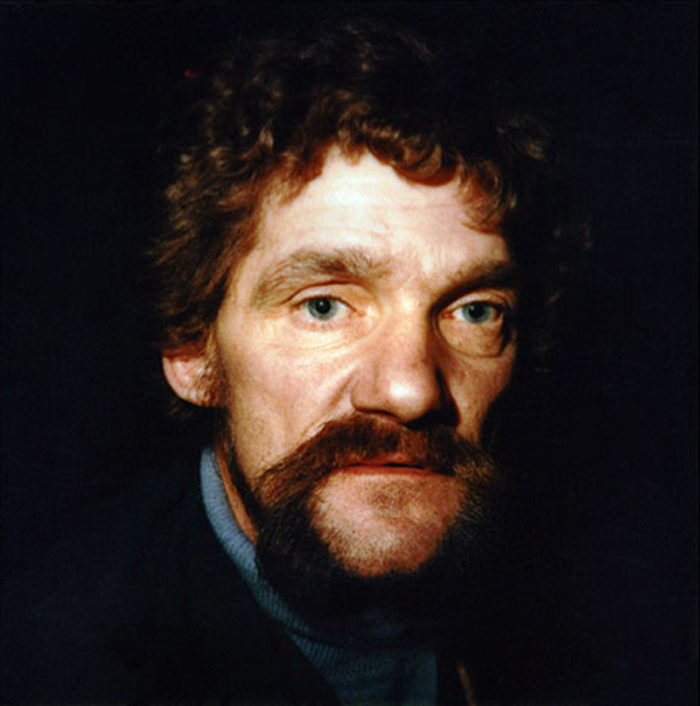

We were not sure at first that selling pictures in the bars would succeed, but in retrospect I can see that our success was virtually assured. Dutch art history is full of portraits of people in bars and taverns, but we were apparently the first to update this tradition with instant photographs. This photo is a particular favorite because it looks so much like a seventeenth-century Dutch painting—not only on account of the lighting, but also because the bearded man looks like a time traveler from another century.

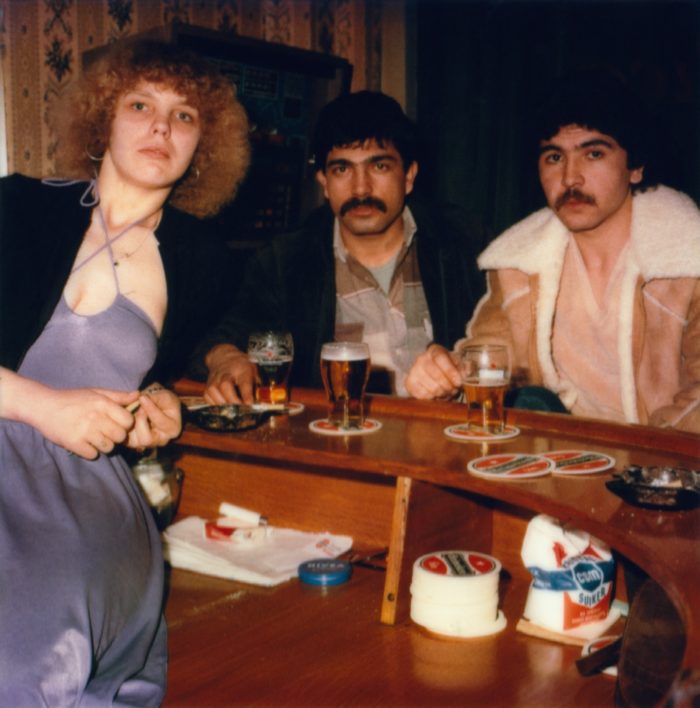

Christien was a young Dutch girl who worked at Camlica, a bar that catered to the Turkish guest-workers in Holland. She liked being photographed, especially with the younger guys, one of whom she identified as her boyfriend. But unfortunately Camlica was not a good situation for Christien. She was usually the only woman in a bar full of men, and on one occasion she ended up getting badly beaten. We all hoped that Christien would not go back to Camlica, but she was back just a couple of weeks later.

The Mexico Saloon was a bar located on the Zeedijk that featured animeermeisjes, women who flirted with customers and got them to buy drinks. Their star was Fifi, who was French. She always wanted pictures, but unlike Nettie at Café Mascotte, who was comfortable in front of the camera, Fifi always needed to be reassured that she looked good. A lot of the pictures we took of her didn’t turn out well because she was fidgety, and would suddenly change her pose just as we were shooting. Every once in a while, though, we got a beauty.

When our photos were featured in the magazine Nieuwe Revu, Jan who owned Café Mascotte, complained that his wife left him because of our picture of him with Nettie and another girl who worked in the bar. We didn’t feel too guilty. I mean, the guy was running a bar with animeermeisjes, and his wife didn’t know? Still, he blamed us for his divorce. That was the only negative feedback we got. But he clearly wasn’t that angry because he continued to let us take photographs in the bar.

Most of the people at the club Jazzland were from Surinam, although there were also some younger Dutch kids. It was one of the few bars where hashish was as common as alcohol. It was at Jazzland that we first encountered a competitor, a man from Uganda with a Polaroid camera, who had had some experience selling photos in London and was passing through Amsterdam. I guess you can say that we had a “shoot off” where we both took pictures, and people started to compare them. We thought he had the advantage, but we had a much better camera and his photographs weren’t anywhere near as sharp as ours. After about twenty minutes he left and we never saw him again.

Madame Arthur in the Red Light District featured transvestite shows. Many customers wanted pictures with the transvestites, but it was mostly the performers themselves who ordered pictures. We had carte blanche over there. When they had a show, we would keep shooting. After the show was over, we would lay out the pictures on the bar, and the performers would go crazy and almost always buy all of them.

The performers at Madame Arthur told us about Bar Festival, the place where they hung out on the days they weren’t working. I vividly remember this photo of Herman and the trans Stien because a videographer was filming us the night the photo was being taken. The video includes the music “Why Can’t We All Live Together” playing in the background. For its regulars, Bar Festival was a refuge, and that Timmy Thomas song was a particular favorite.

Café Rex was full of single people in their twenties and thirties, flirting and looking for dates. The customer who stood out for us was Piet, a Café Rex regular and a serial photograph buyer, who systematically accumulated a large collection of pictures with different women. We often wondered what Piet did with all the pictures. He definitely was proud of them, and when we asked people to provide us with duplicates for our exhibition, Piet contributed 4 or 5 photos, and posed by them at the opening.

Selling Polaroids in the Bars of Amsterdam, 1980 will be widely distributed in The Netherlands, but it will receive only limited distribution in the U.S. Those who contribute 50 euros to our Voordekunst campaign will receive a copy of the book.