Watergate Courtroom Sketches by Freda L. Reiter, 1973–75

A Republican president on the verge of impeachment, accused of obstructing an investigation into the theft of information from the Democratic National Committee—this was the story in 1973 and 1974, when members of Richard Nixon’s administration went on trial, and the phrase “Watergate” became shorthand for a many-layered political scandal. Artist Freda L. Reiter (1919–1986) captured the drama in pastel drawings broadcast on ABC-TV: courtroom scenes drawn from life, as well as visual recreations of Nixon’s tape-recorded conversations, and even of the moment he resigned from the presidency.

Watergate was as much a media event as a political one. The story that broke on June 17, 1972, when five burglars were caught wiretapping the DNC headquarters at the Watergate complex, blew up when investigations by the Washington Post and other papers tied the burglary to Nixon’s White House.

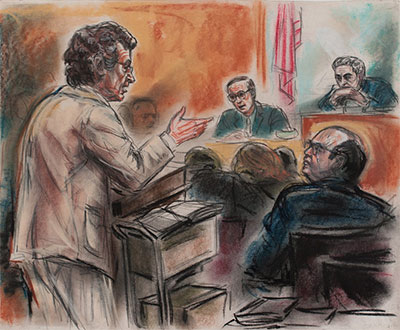

The Senate hearings broadcast live in spring 1973 drew record ratings. Nightly news shows covered the multiple trials that led to Nixon’s resignation on August 8, 1974, and finally to the conviction of several of his top aides on New Year’s Day 1975. Since cameras were banned from courtrooms, news outlets depended on professional sketch artists like Reiter for visuals.

Even in childhood, Freda Leibovitz and her twin sister, Ida, were acclaimed for skilled drawings from life; by age 12, they were spending summers selling portraits at the Cape May resorts on the Jersey Shore. After studies at the Moore College of Art and Pennsylvania’s Academy of Fine Art, Freda moved to Mexico to study and work with Diego Rivera. Under her married name, Reiter began doing black-and-white courtroom sketches for the Philadelphia Inquirer newspaper in 1949, and switched to color pastels after moving to ABC-TV in 1966. (Her sister, now Ida Dengrove, became chief illustrator for rival NBC News.)

When Reiter was assigned the Watergate burglary trial, in 1973, she had no idea that she would be spending the better part of two years in Washington. As the story deepened, Reiter covered all the trials and hearings. To provide sufficient visuals for the substantial airtime allotted to the story each night, she made multiple sketches a day: close-up portraits, as well as wide-angle views of the courtroom incorporating as many as 28 figures.

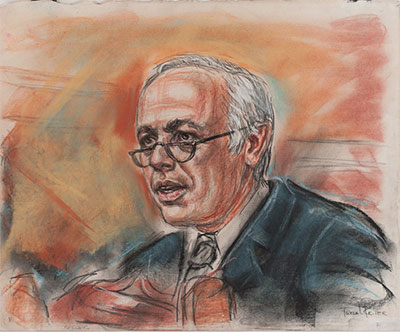

Reiter’s eye for facial expressions and gestures helped her capture the personalities of key figures, just as her impressionistic use of color conveyed the heightened mood in the courtroom. Despite the pretense of objectivity, Reiter’s sketches betray a point of view. As the prosecution closed in, and Nixon’s approval rating continued to sink, the trials took the form of a suspenseful television drama, with its heroes and villains. One need only compare Reiter’s depictions of prosecution witness John Dean (youthful and stoic) and defendant John Ehrlichman (wrinkled and snarling) to see her stance on the proceedings.

At the heart of the Watergate scandal were Nixon’s secret audiotapes, first revealed during the Senate hearings, and only released after the Supreme Court’s ruling, in United States vs. Nixon, against the President’s claim of executive privilege. Several of Reiter’s courtroom sketches depict defendants listening to the declassified tapes on headphones. To accompany the tapes’ playback on TV, Reiter also re-created the scenes of their recording, drawing her own envisions of Nixon’s Oval Office meetings.

Reiter’s drawings continue a long tradition of journalistic illustration, which was generally excluded from the mainstream art discourse. Today, in the wake of Pop, and artists’ embrace of mass media, it’s not shocking to see the art media take notice of the current show of courtroom illustrations at the Library of Congress. It seems fitting, even necessary, to return Reiter to a fine-art context such as Gallery 98.

From the Collection

Sold