Roger Lannes de Montebello (1908–1986): A 40-Year Quest for 3-D Photography

Marquis André Roger Lannes de Montebello (1908–86) is not a name familiar to the art world. Although Philippe de Montebello, the former Metropolitan Museum director is well-known, few people have heard about his father Roger de Montebello and his life-long creative obsession with three-dimensional photography. As much inventor as artist, de Montebello’s achievements have been undercut by new technology. In the words of Philippe de Montebello, “By now, I would have thought, holograms and beyond, that his 3D process is little more than a curiosity.”

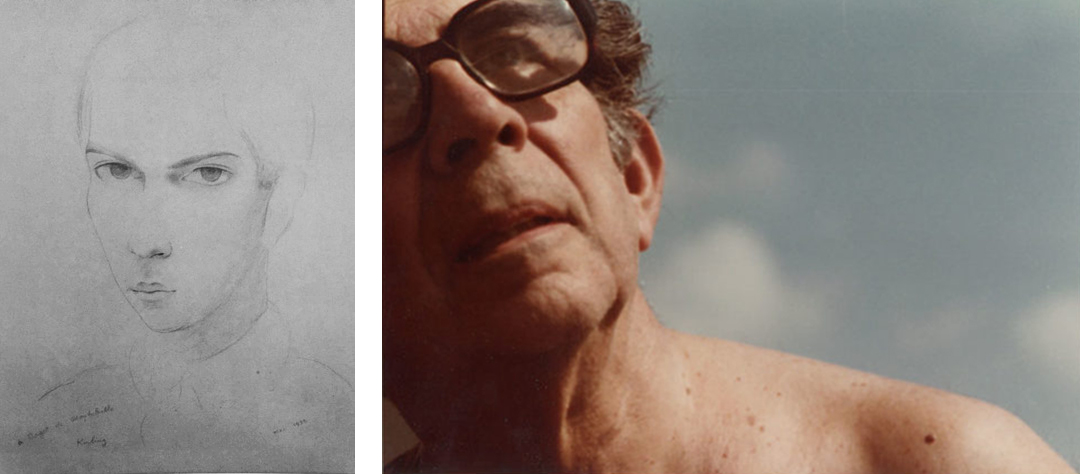

Roger de Montebello began his creative career in the rarefied pre-World War II French art world. Before turning his creative energy to 3-D photography he was a portrait painter and an art critic. His wife, Germaine Wiener de Croisset, was the half-sister of Marie-Laure de Noailles, the famous patron of the Surrealists. De Montebello himself collaborated with Salvador Dali, who shared his interest in optical effects.

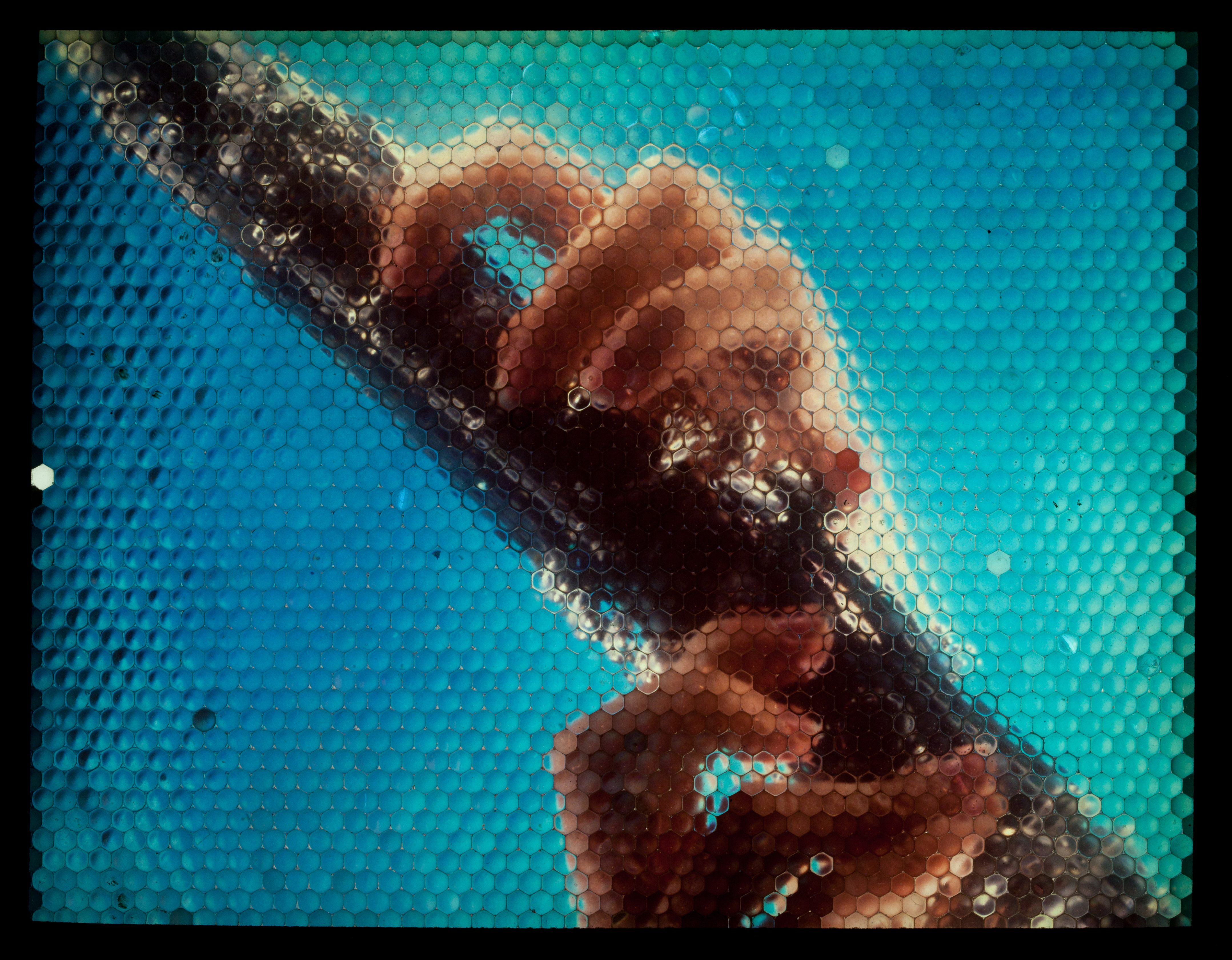

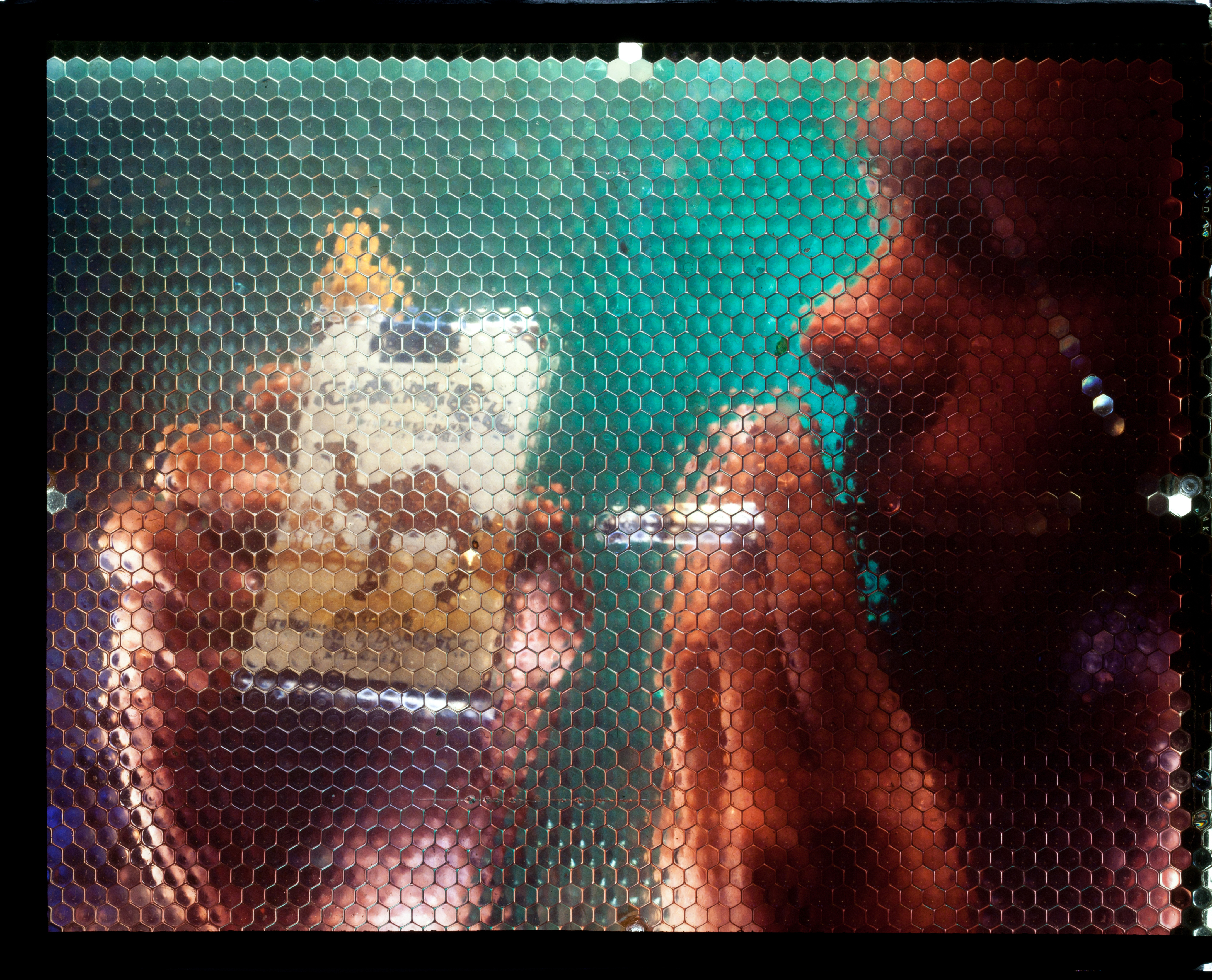

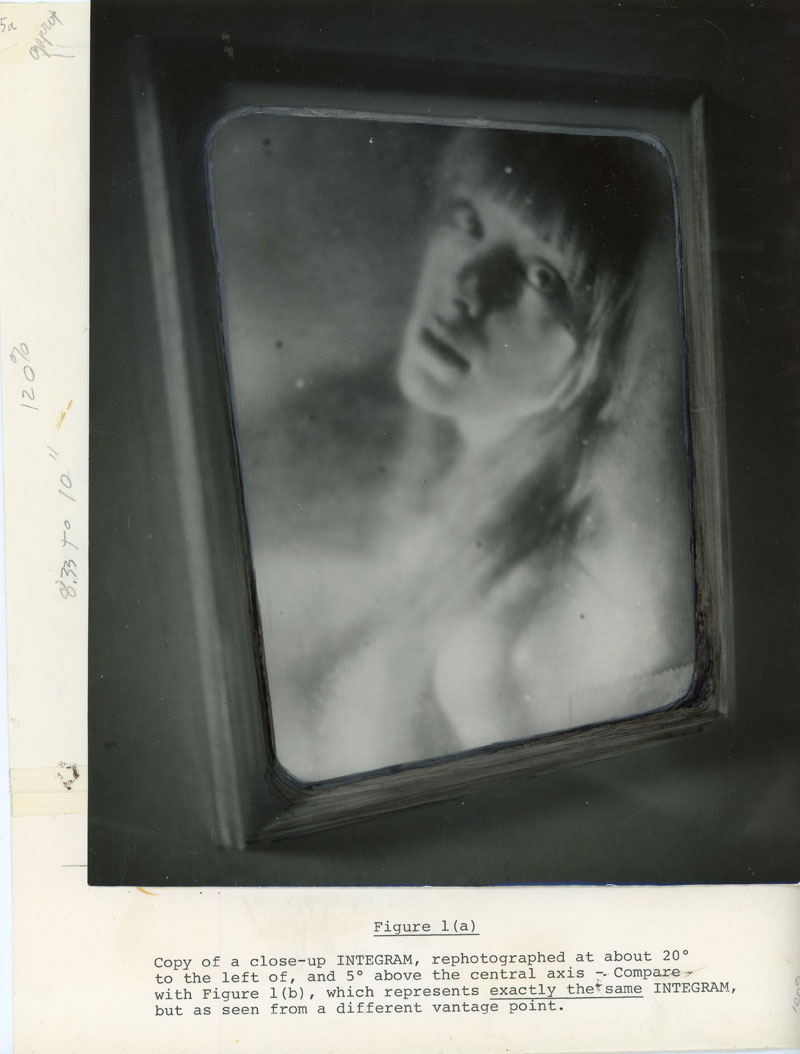

De Montebello described his quest for a true 3D image as follows: “Imagine… a photograph of a woman wearing earrings adorned with a glittering De Beers diamond. You see one earring. Walk slowly past the photograph so you are viewing it from gradually changing angles… The earring from one ear recedes from view while its twin [appears] in turn on the other ear.”

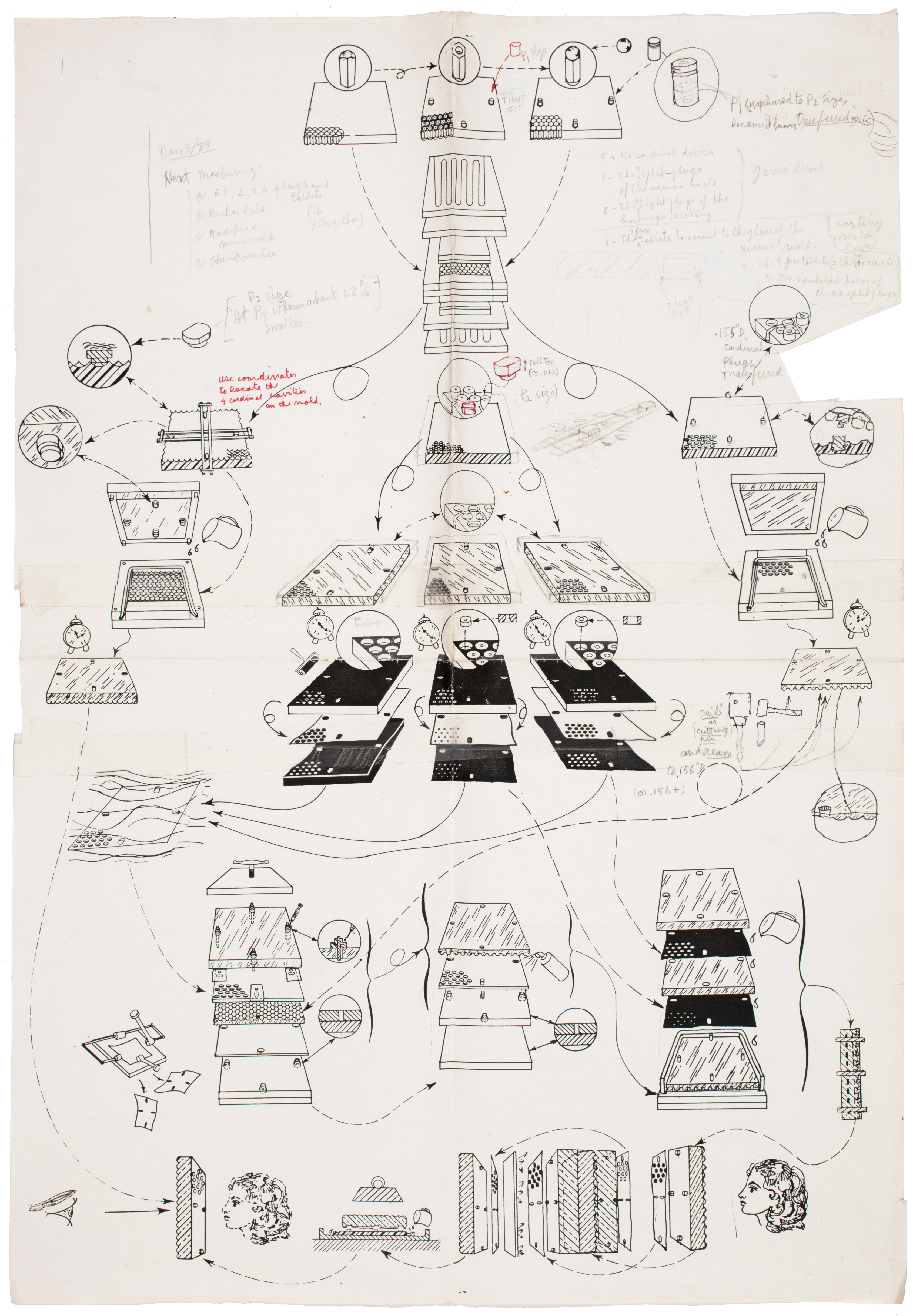

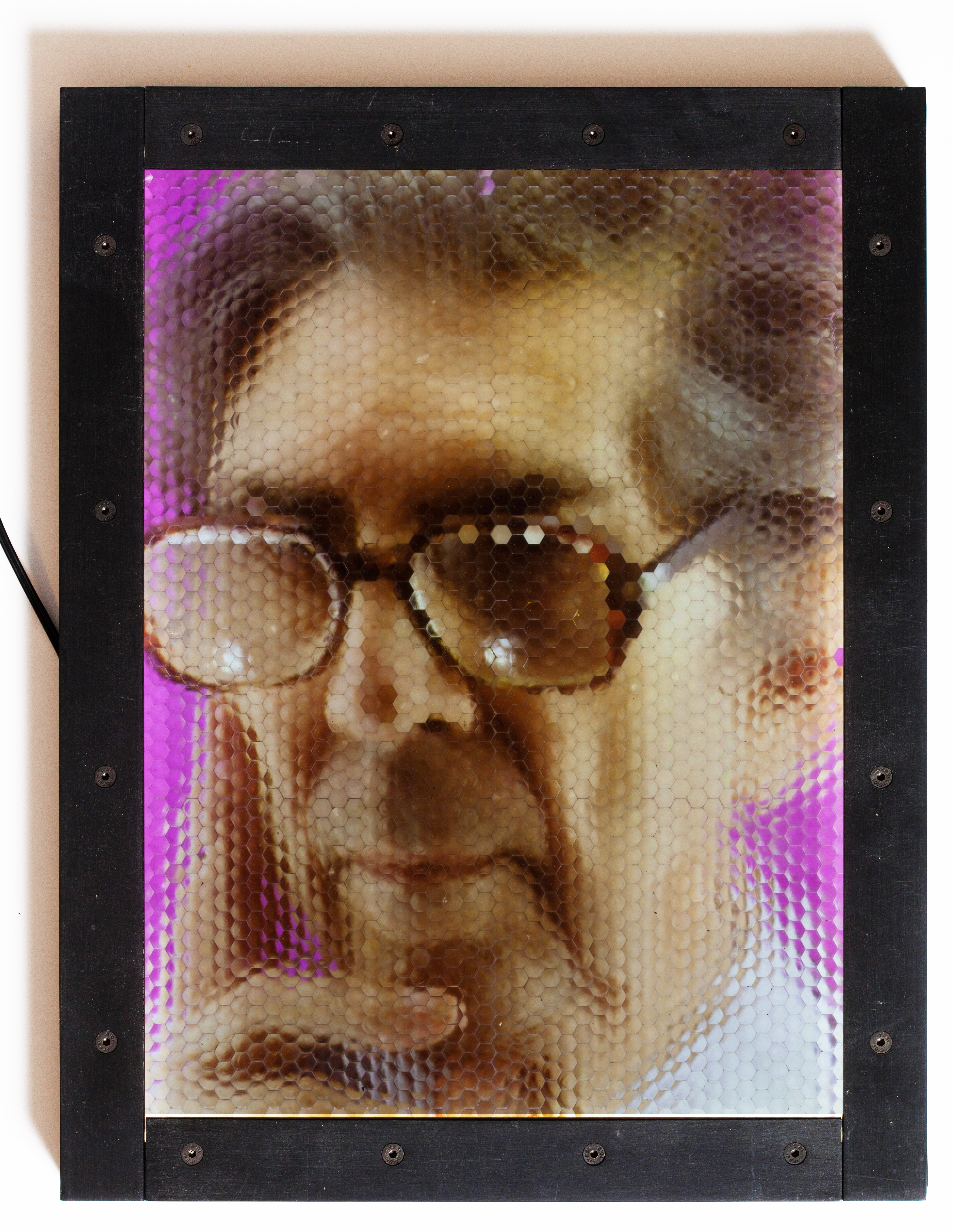

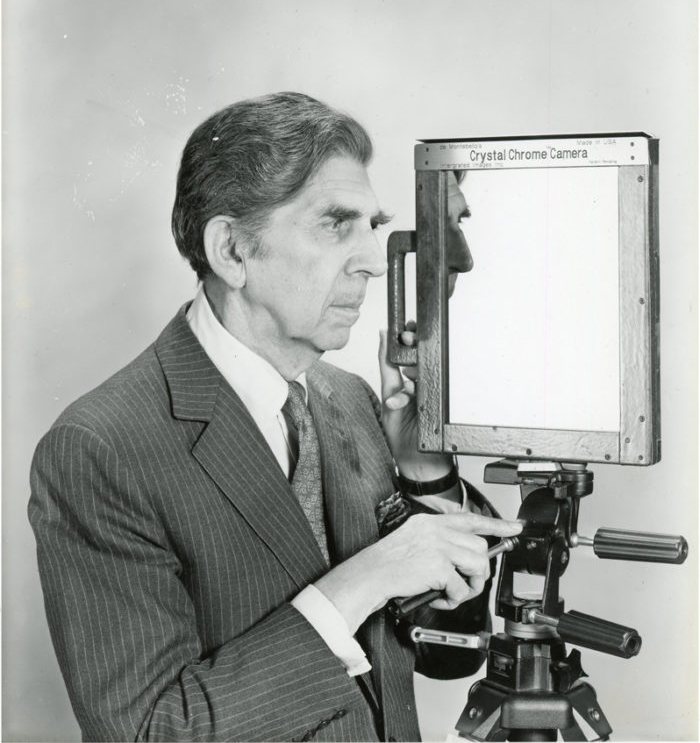

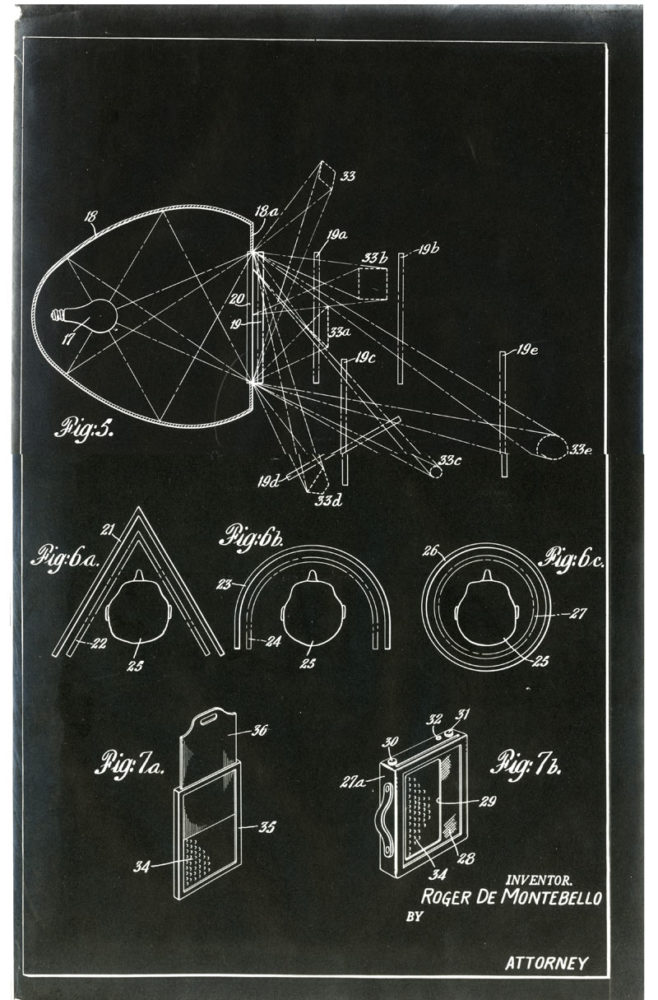

Building on theories first postulated in the early 20th century, de Montebello developed a new type of camera that produced individual transparencies each consisting of 2,644 separate exposures. When such a transparency is seen through a “lens-viewing screen” (another invention of de Montebello’s), the multiple exposures merge into a single 3-D image that changes depending on the viewer’s position.

In his early patents de Montebello called his technique “Space Photography.” He also used the terms “Integral Photography” and later “Fly’s Eye Photography.” Despite the vast amounts of time and money he devoted to the project over a 40-year period (first in France and then the United States), de Montebello was never fully satisfied with the results, especially in terms of his invention’s commercial application.

Today, new technology—holograms and computer-assisted digital animation—have totally bypassed de Montebello’s conception. Although his work may now appear to be a relic of an increasingly remote analog era, both the photographs and de Montebello’s finely executed working drawings are intriguing. He may never have achieved the seamless 3-D realism that he sought, but his Fly’s Eye pictures, best seen mounted on a light box, have an uncanny, otherworldly quality.

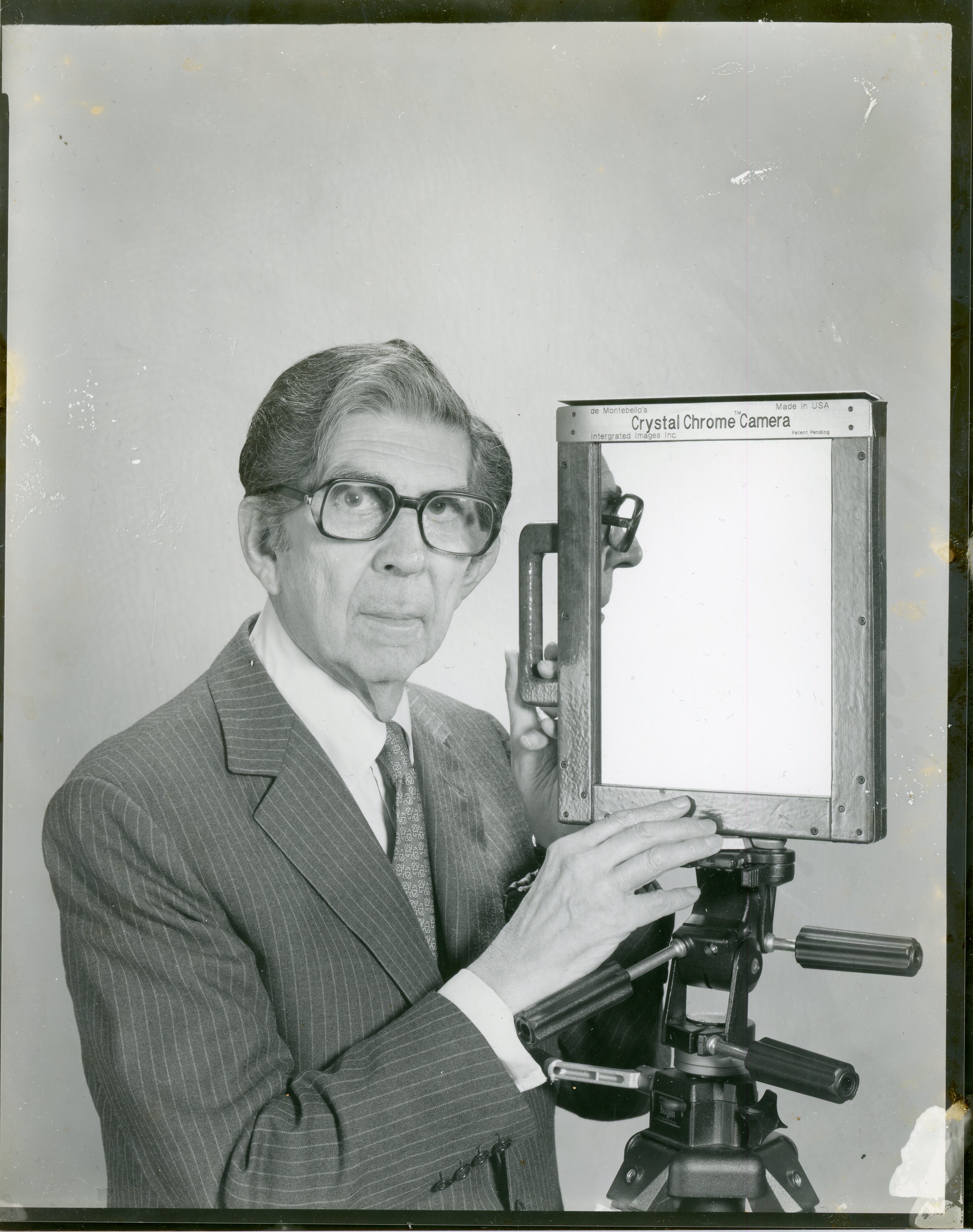

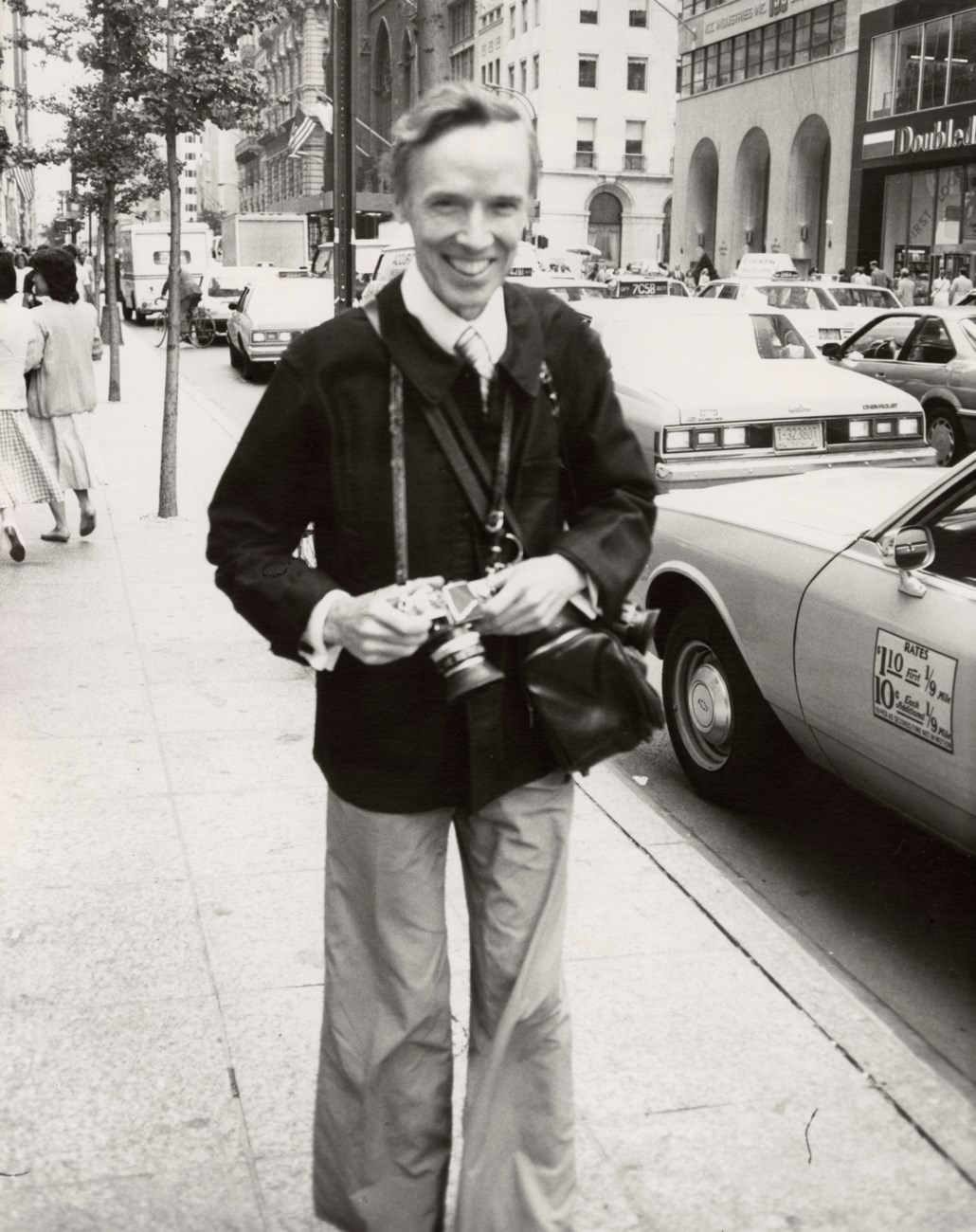

Gallery 98’s collection of Roger de Montebello materials includes many completed Integram 3-D photographs, each consisting of an original photo transparency and a lens screen that integrates the multiple exposures on the transparency into a 3–D image. The collection also includes de Montebello’s “Crystal Chrome” camera, the casting molds used to make the lens screens, notebooks filled with his notes and drawings, meticulous renderings on graph paper and vellum, documentary photographs, and various other ephemera.

This material was acquired from M. Henry Jones who worked with de Montebello at the Globus Brother’s studio from the mid-1980s right up to his death, and continues today to improve the Integram process by using new computer capabilities and fabrication techniques. Jones’ recent Integram 3-D photographs are notable for their larger size and seamless 3-D effect. M. Henry Jones’ relationship with de Montebello is just one aspect of his broader interest in art and technology. Visitors to Gallery 98 may remember an exhibition of Henry Jones’ earlier photo cut-outs.